by Maeve Evelyn Reilly

INTRODUCTION

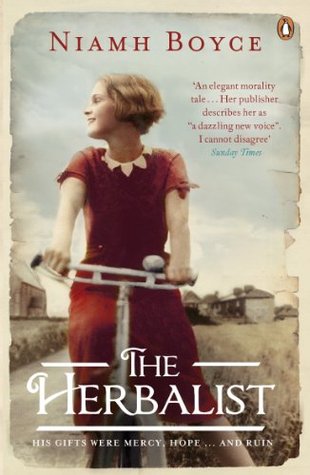

Niamh Boyce’s novel, The Herbalist (2013), reflects much of the repression and abuse suffered by women in Ireland during the twentieth century. In this analysis of her book I hope to make apparent how Boyce’s attempt to resurrect the lost voices of those forgotten Irish women succeeds without resorting to any homogenisation of their differences. I employ both cultural materialism and feminist theories in order to demonstrate how this novel portrays a patriarchal hegemony which maintains its suffocating rules and norms over the female characters, not just by the use of force, fear and ignorance, but by means of a sadomasochistic consensus and a wilful hypocrisy on the part of the community, which is ultimately self-destructive for that same community. This patriarchal hegemony will be seen to cause divisiveness and silence amongst the women, thereby reinforcing its dominance. In addition, the transference of the community’s fantasies, guilt and anger onto the outsider by the frustrated community is shown to be a consequence of this repressive hegemony. Finally, the wonderful gyn/affection and solidarity to be found amongst the marginalised and ostracised women in this book will be discussed.

Niamh Boyce is an Irish poet, novelist, artist and feminist. Apart from being well versed in the literary tradition, she is also influenced by her own experience of having lived through a period in which scandals of abuse committed by the Church and Irish State have shaken the country. “It was a very male world […] We´re lucky to be liberated and forget what it was like for our mother´s generation” (The Irish Times 05.06.13). She won the Hennessy XO New Irish Writer of the Year and the Emerging Poet Category in 2012 and published her debut collection of poems Inside the Wolf in 2018. Her interest in fairy tales and folktales is reflected in her poems “I love […] the magic, the strange creatures, the transformations, the danger, the dark woods” (O’Connor 22.08.18), and in The Herbalist where the appearance of a supernatural double, a ‘fetch’, forewarns the death of Aggie, and the ghosts of Aggie and Rose inhabit lanes and rivers. Boyce´s second novel, Her Kind, was published on 4th April 2019 by Penguin and is based on the Kilkenny Witchcraft trials of 1324. The Herbalist is Niamh Boyce´s debut novel. It was published by Penguin Ireland in 2013 and won the “The Sunday Independent Newcomer of the Year Award” of the same year (The Sunday Independent 26.11.13).

The Herbalist is based on a piece of news that Boyce came across in 1990. The item, dated May 1942, referred to a herbalist, a “coloured man arrested for serious offences against girls” (The Irish Times). Boyce grew up in Athy, County Kildare, the rural market town where the original case took place, and thanks to a local historian she discovered that “[t]he real herbalist – Don Rodrigo de Vere – was charged with ‘procuring miscarriages’ for women” (The Irish Times). Boyce suspected this herbalist might have been a scapegoat and nearly twenty years later felt compelled to write about the case: “Other voices began to speak to me as I wrote, and they were all talking about the same person – the herbalist. Some called him a scoundrel, some a saviour” (Writing.ie 06.06.13).

Although the novel deals with Ireland´s dark past regarding its oppression of women, it is also very witty: “I found the rules of the society I grew up in quite ridiculous, so was always irreverent, though not always vocal. The silence came from fear. […] So perhaps humour was a survival mechanism” (O´Connor). Boyce’s novel is set in a market town in rural Ireland in 1939 and commences with the arrival of an exotic Indian herbalist in the market square. The plot revolves around the catalytic effect this outsider has on the town and, in particular, on the women who become involved with him. In order to fully appreciate this novel, we need to look at the historical context in which the story unfolds.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

During and after the great famine of 1845-9 the Irish population fell by 20% due to starvation, disease and emigration. Poverty, the low status of women, and the need for marriage dowries, all combined to cause two million women to immigrate to the US or Canada (Jackson, 1984; 1005-7). By the turn of the century the percentage of women emigrating outnumbered that of men, and the number of teenage girls leaving had doubled. In a country where employment was denied to the majority of women, and poverty was rife, the only roles left open to women were those of nun, wife or prostitute. In Kildare, during the nineteenth century, destitute women, mostly prostitutes and some with children, lived in ditches or hovels out on the plains of the Curragh rather than enter the workhouses. Known as the Wrens they forged a community and support system amongst themselves. They were frequently beaten by drunken soldiers, attacked by gangs of men, whipped by priests, and reviled and ostracised by the townspeople (Greenwood, 1867).

During the eighteenth and nineteenth century Magdalene asylums and workhouses were set up to house and rehabilitate prostitutes and destitute women in Europe, Australia, Canada and the USA. The arrests of impoverished women for soliciting in Dublin city in 1870 totalled 11,864 (Luddy, 2011; 342). Irish society was one where authority came in the form of the male, be it priests and bishops in charge of the convents; prison and police officers controlling the lives of prostitutes (345); or husbands holding legal sway over the lives of their wives and daughters. By the twentieth century all Irish Magdalene asylums and mother and baby homes were run by nuns. In both institutions women had their babies forcibly removed. Some babies were adopted, others sent to orphanages, and many died. “Because illegitimacy was seen as a crime, both mother and child suffered while the father, often unnamed, felt few or no official repercussions” (McCarthy 14). Young women were incarcerated in the Magdalene Laundries because they were pregnant, orphans, non-conformists, impoverished, deemed to be promiscuous, or considered to be a temptation to men. These laundries became slave labour camps where many of the women died in service. The Irish State supported these institutions: “labor factory laws, the modern Irish Constitution, along with the Catholic Canon Laws, came together in a silent marriage that allowed few rights for the Irish female, and no rights within the Irish reform institutions” (McCarthy, 2010; 13). Then there was the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), set up by upper-class Anglo-Irish women in 1889 to ensure the safety of children. The NSPCC inspectors, known as the Cruelty Men, would forcibly remove babies and children from single mothers and poverty-stricken families. Apparently, class prejudice played its role in the standards required for parenting (The Irish Examiner 01.08.18).

Despite the involvement of women in the Irish fight for independence and the promise made in the Proclamation of the Republic of 1916 to guarantee “religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens” (The Independent 25.03.19), women did not achieve equality or justice. The Irish Constitution of 1937 drawn up under Eamon De Valera ensured that a woman’s place was in the home: “The State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved” (Cullingford, 2001; 227). De Valera, a strict Catholic with misogynistic tendencies, gave the Church special powers and rejected socialism. Although picture houses were deemed detrimental to the renewal of Irish culture and nationality, they also served as a focus on which to place the blame for society´s ills. Ireland´s first Film Censor proclaimed in 1924 that “the greatest danger to Ireland came not from the Anglicization of Ireland but from the Los Angelesation of Ireland” (Rockett, 1991; 18). Despite heavy censorship, cinema-going was tolerated. Following the creation of the Committee on Evil Literature in 1926 and the Censorship of Publications Board in 1929, novels were frequently banned. During the 1930s the Irish State proceeded to remove its links to British rule, however, the State’s nationalist and patriarchal catholic principles were superimposed upon what remained of the old British patriarchal ascendancy and its class system.

ANALYSIS

Jan Assmann claims that everyday communications have a maximum period of recollection of one hundred years. I believe that the memories of most women over the last millennium fall into this category. Assmann further claims that cultural memory is a lasting store of knowledge which serves to assist in one´s self-identification (Assmann, 1995; 127). As western cultural memory has been predominantly patriarchal for centuries, it follows that women have had few if no cultural points of reference for their identities other than those forged for them by men. Michel Foucault wisely conceives of power as a co-dependent of knowledge, where the practice of remembering and forgetting forms part of that power relation. Thus he believes it vital to resurrect the subjugated knowledges of the (un)truths that have been excluded and forgotten (Medina, 2004; 9). Consequently, it is clearly essential to unearth and insert the memories excluded from our cultural memory, such as those of women, in order that they forge their own identity and acquire the power necessary to seek justice.

According to Antonio Gramsci, hegemony is an official dominant central system of control, both disciplinary and consensual, whose culture saturates the consciousness of a society to the point of appearing natural (Williams, 1973; 8). It dominates by means of an “ascendancy achieved through culture, institutions and persuasion” (Connell, 2005; 832). Although alternative emergent elements may be incorporated, oppositional ones will not be tolerated. The hegemony in Ireland functioned in such a fashion, saturating the minds of its people with its class system, religious indoctrination, and concept of female inferiority.

Over the last couple of decades there has been a great explosion of women and men writing novels in Ireland. This productivity springs from a newly found confidence and freedom of expression combined with the need to come to terms with a dark past. Mikhail Bakhtin argues that the novel resists hierarchy due to its ‘dialogism’, and that within this medium it is possible to find a healthy contestation between multiple voices with multiple ideologies (Bauer and McKinstry, 1991; 9). Given that Boyce’s interest lies in resurrecting hidden stories and the voices of those who were silenced in the past (A Writing Blog 21.10.18), it is clear to me that she has found the perfect medium in which to exhume these buried voices. She gives life to the real fears women had during the last century in Ireland and in so doing tries to recover these forgotten, unwritten lives, and cast them in the light of twenty-first century interpretation. Her novel foregrounds a dialectical struggle between the hegemonic truths and the multiplicity of the marginalised women´s voices. Each character interprets the world through their own personal lens, which is framed by that of the hegemony. These multiple voices are full of dialogic conflict and resist any settlement or totalising perspective.

The story is narrated by the alternating voices of four women offering their differing views and experiences. The sixty-seven chapters narrated by Emily, Sarah and Carmel are numbered and woven like a tapestry, whereas the unnumbered chapters narrated by Aggie appear as dropped stitches, with the open stitch of the last chapter akin to a new beginning.

Emily

The main narrator in The Herbalist is Emily, a precocious sixteen-year-old girl who loves dressmaking, which makes her the perfect person to stitch this tale together. As a first person narrator, her sarcastic humour has a strong impact on the reader. However, her character is somewhat conflictive in that she is portrayed as clever and observant yet foolishly romantic and bitterly jealous. As a consequence of her mother’s marriage to a travelling salesman, a violent drunken womaniser, her family is viewed by the community as lacking respectability. Doctor Birmingham´s wife, Grettie, through jealousy and snobbery, marginalises Maureen to the extent that Emily is unaware the women are cousins. Emily deeply resents her family’s marginalisation. Although she is quick to point out the hypocrisy and snobbery of the townspeople, she is not without prejudice herself. She thinks Sarah conniving for having taken her job: “She had taken my place with everyone, blinded them with her charm” (Boyce 101), and her lower class status causes her to suspect that the doctor’s daughter, Rose, is toying with her brother, Charlie. Nonetheless, Emily is aware that her family uses Aggie, the town prostitute, as someone to look down on. It is Emily who introduces us to the herbalist: “He was the lightest thing there, the one they called the black doctor. […] The men spat about dark crafts and foreign notions, but the women loved him” (1). The fact that the herbalist sees Emily with new eyes liberates her from her sense of entrapment in this class system. However, her romance with the herbalist gives her a reality check when she discovers that he performs abortions.

Emily views the world through the romantic lens of Hollywood, influenced by its illicit love affairs, glamour and fashion. She sees her mother as a Maureen O´Hara lookalike and goes to great lengths to reproduce glamorous dresses so she can glide through town like Greta Garbo. She is therefore susceptible to Aggie´s foretelling of the approach of love and the townswomen´s excited talk about the herbalist. Her infatuation is readymade, and she becomes besotted by the herbalist in a half fantasy world of her own creation. She imagines herself and the herbalist in starring roles where they escape into some ‘happy ever after’. As Aggie observes: “She stops short of wrapping herself in butcher’s paper and delivering herself to him” (250). It is widely accepted that Hollywood nurtured in women a passiveness and a wish to be desired by the active male hero, while at the same time negating female friendship through the representation of other women as competition. Likewise in the novel, Emily perceives the eligible townswomen as opponents in her battle to win the herbalist’s heart, and this competitiveness, along with the death of her mother, leaves her vulnerable to her own fantasies.

According to Laura Mulvey (1989), cinematic scopophilia, or the desire to see, consists of a male voyeuristic gaze and a female narcissistic identification with the object. Emily appears to have become her own object of desire through over-identification with fetishised female stars and she often appears to be giving some grand performance. It can also be argued that she has merged with her object of desire in a pre-oedipal desire for her dead mother. Mary Ann Doane tells us that “the female spectator of those melodramas is involved in emotional processes like masochism, paranoia, narcissism and hysteria” (Smelik, 2007; 49). Certainly, these traits are evident in Emily when it comes to her relationship with the herbalist.

Nonetheless, Emily is searching for knowledge outside the framework of the town, and is seeking power in her efforts to find work. She is intuitive enough to sense that Doctor Birmingham is a danger, and the fact that she suffered an exorcism as a child “a casting out” (Boyce 75), points to a rebellious nature. Moreover, as she is often parodying Hollywood actors and performing humorous critiques of the townswomen, especially Carmel: “Plums in her mouth, shite on her shoes” (36), her actions can be interpreted as challenging the hegemony’s authority by dialogising meaning in a Bakhtin type of carnivalesque mockery. Throughout the novel Emily borders on being oppositional to the hegemony and is in danger of being labelled a woman of disrepute. She represents an emergent element in society, struggling against the patriarchal class system, and her character is a harbinger of change and hope for the future. Although she is to be incorporated into the hegemony through ownership of the shop she inherits from Birdie, her metamorphosis into an exotic outsider – portrayed in similar terms to those of the herbalist: “[s]he’s nothing less than a magician” (308) – makes her future uncertain.

Carmel

Both Carmel and Sarah´s tales are narrated in a free indirect discourse of first and third-person with the result that their subjective viewpoints have less impact than Emily’s. Carmel is depicted as holding a strong, respectable middle class position in the community. She lives in compliance with the hegemony and the position of power it offers her, however, her inner conflicts cause cracks to appear in her conformity. Carmel is quick to judge others whilst unabashed at her own hypocrisy. Although she is shocked that Birdie rents illicit literature, she desires access to it, and out of resentment nicknames her “Lady Chatterley”. Later, she has no qualms about renting the censored books her brother, Finbar, gives her but she hides her criminal activity from her husband, Dan, whom she considers priggish and hypocritical. She will not admit that she enjoys reading banned novels, and although she finds Dan’s demands that she wash Aggie’s money ridiculous, she also contemns Aggie. Moreover, Carmel resents Grettie´s snobbery, yet disparages Emily as a silly lower class girl, and though she lords it over Sarah, she wishes Sarah would confide in her. She is shaken to discover that the herbalist, Emily or Sarah could be in a position to contest her authority.

Carmel suffers the cruel power of a hypocritical Church which dominates the minds of people who ache to believe in and live up to its perverse ideals. The Church´s negation of the right to bury her unbaptised baby in the Church cemetery causes her to obsess about the baby´s soul being lost in limbo. She desires the only legitimate role assigned to women by the hegemony, that of mother, however, she is unable to conceive and her credulous devotion to the cult of the Virgin Mary proves futile. Consequently, she turns to the herbalist for help, unwittingly becoming addicted to his laudanum and her own Buckfast wine. Carmel reverts to a world of ghosts, both her mother´s and baby´s, and loses her faith “God. How could she believe in Him now? Yet she didn’t dare say that out loud” (40). Her internalised misogyny and masochistic compliance to a sadistic system unhinges her mind and causes her to become vicious enough to blackmail the herbalist into forcing an abortion on Sarah, “a whipper-snapper whore” (273). She is representative of the wilful hypocrisy and sadomasochism of those that comply with the hegemony and the only way she can find peace of mind is through suicide.

Sarah

The character of Sarah resurrects the knowledge that many innocent women were forced into impossible positions where they had no choice but to sacrifice their principles in order to survive. Sarah is a naïve country girl who is shocked to discover Carmel possesses a novel about a thieving prostitute, Moll Flanders, and when her aunt Mai explains how a girl was obliged to fool her husband into thinking that her baby was his, she is outraged by the deceit. I believe her aunt Mai represents the knowledge midwives held, one which was subjugated, not only because it was a threat to dominant male medicine, but because female power had long been feared and categorised as witchcraft. Sarah’s marginality results from the fact that her aunt is a midwife and therefore regarded with suspicion, and that she is most probably Mai´s illegitimate daughter: “Was my mother quare?” […] Sarah said gently, looking into Mai’s eyes and holding her gaze. A soft oh slipped from Mai’s lips and a tear ran down her face” (243).

Finbar, the headmaster, convinces Mai to send Sarah to work in Carmel’s shop in order to distance her from his son, James. However, Sarah’s ignorance of her marginalised position makes her unaware that James has no intention of legitimising their relationship, and on the night of her departure, James rapes her. Swiftly, she is made aware of the threat of the Magdalene Laundries and of the fact that a woman’s capacity to procure the protection of marriage depends on her status and wealth, so when she discovers she is pregnant, she recognises the danger she is in. The perverse morality of a hegemony that would remove her baby and incarcerate her, forces her to put her reputation at risk and resort to deceit. Although she considers the herbalist an itinerant hawker, she works with him and gambles at his parties in order to earn her passage to England. More than her desire for Dan, it is her desperate need to secure male protection for herself and her unborn child that pushes Sarah into an affair with him, in the hope he might believe her baby his. Sarah has been contaminated by the perversity of the hegemony, “[h]ow could that even cross her mind, to be so deceptive, to sink so low?” (234), but she has been given no choice. Eventually she will be rescued from the clutches of the herbalist by the novel’s anti-heroes, Aggie and Emily, and will secure a life of obscurity under the protection of Matt, thereby existing as a non-threatening alternative to the hegemony: “She was just a stranger who had worked in the town for a summer and then disappeared” (308).

Aggie

Aggie joins in the dialogue late in the novel and we discover she is speaking from beyond the grave whilst answering dead Rose´s questions. This use of ghosts can been interpreted as a trope employed to express the trauma that Aggie and Rose experience, which cannot be voiced in life: “Tell it and tell it and there’ll be no shame, only the facts of the matter and the question of who’s to blame” (247). According to Julia Kristeva, language is a process where two elements co-exist: the symbolic order which facilitates communication, and the semiotic which destabilizes the urge for fixity and facilitates new meaning. Aggie´s chapters in this book exist on that threshold between control and disruption, providing the “intertextuality” necessary to give new meaning to the collective memory (Morris, 1995; 151). As the town prostitute, Aggie is an outcast who initially befriends the herbalist, believing they are of like ilk: “We were in the same kind of business. The same fake How Great Thou Art. And afterwards the exact same ‘I have your few bob, now feck off’’ (Boyce 193). However, she begins to hate him after his fat landlord rapes Emily. Aggie’s way of life is a threat to the hegemony so she will not be incorporated, she can only be tolerated on the margins and any opposition on her part might result in her elimination. She has in the past confronted society in the act of punching the nun who took her baby away, however, she considers her ensuing imprisonment a lucky escape from being locked up permanently in a laundry. Consequently, she flees respectable society to become a prostitute who appreciates the freedom of living on a barge: “Why do women hold on so fierce to their good reputations? All a reputation does is stop you doing as you please” (223). This puts her in the juxtaposed position of having power over men while at the same time being at their mercy. According to Nancy Chodorow, the psychological dilemma of rejecting femininity in one´s own nature in order to conform to the norms of society incites men to commit violence against women (Gardiner, 2012; 610). As previously stated regarding the Wrens of the Curragh, men performed barbarities on prostitutes with total impunity, and Aggie suffers this misogynistic violence in the knowledge that no one will defend her. Down the centuries, the story of the prostitute has been obliterated or dehumanised. Boyce raises the prostitute’s voice from oblivion through the character of Aggie. She represents the many strong and rebellious girls and women whom the hegemony in Ireland would not tolerate and set out to obliterate.

Rose

Rose is the silent voice of this tale, her story camouflaged – a subjugated knowledge. She is the only child of an upper class family and as such is both part of the dominant hegemony and its victim. Her father, Doctor Birmingham, beats and rapes her, and her mother, Grettie, not only refuses to believe her daughter, but controls her every move to avoid her talking, eventually covering up the cause of her daughter’s death. Grettie´s wilful and hypocritical complicity with the hegemony makes her complicit in Rose´s demise, and this in turn results in the break-up of her marriage, leaving her to live alone with her guilt and alcohol. The hegemony is therefore seen to be destructive for the women who suffer and fear it, such as Rose and Sarah, for those who sadistically and masochistically comply with it, such as Carmel and Grettie, and for those who rebel and try to live in its shadow, such as Aggie. Many of its victims are seen to turn like rats caught in a cage and perform cruel acts either to protect themselves or to maintain their position within society. Nor is Emily spared contamination by the hegemony’s perversity as she is left no recourse to justice other than to give evidence against the herbalist, feigning that she suffered the abortion Rose had. Nevertheless, we catch many glimpses of rebellion, be it Sarah wishing she could have the adventures of a man, Aggie demanding she drink at the bar with the men, or Emily mocking male authority: “There was always a man being called in to deal with me: it used to be my father, then it was the priest, now it was the doctor. Who next, the plumber?” (Boyce 60).

The Hegemony’s Divisive Silence and Sexual Repression

For centuries women have been portrayed as the opposite of the perfect Vitruvian male by which everything is measured, the negative other on which men could edify themselves. Women were not worthy of full rights as citizens and were subjugated to male dominance in the guise of protection. This disempowerment of women and a patriarchal desire to control female sexuality caused chastity to become a prized quality in a woman, and women came to internalise male prejudices against their gender. This in turn made women nurture a disgust for their own sexuality, and for any overt demonstration of sexuality in other women. This can be seen in The Herbalist where Aggie is reviled by the townswomen for being a prostitute and Sarah is blamed for being raped: “‘You led him on. These lads aren’t in full control.’” (292). Although sexual attraction is perceived as an important factor in obtaining the protection of a husband, it is also an invitation to ruin, a contradiction that women cannot surmount. The authority held by patriarchs to punish women’s sexuality looms in the novel in the form of Doctor Birmingham, Finbar, the Magdalene laundries, and the Cruelty Men, however, the fear they inspire is not spoken of openly, but sensed like a scary story for children, lending it more power. The women are seen to live in constant fear of losing their respectability, and this fear breeds an atmosphere of competitiveness and secrecy.

Mai is accustomed to secrecy. By concealing the confidences of the pregnancies and sexual diseases she deals with she lends them invisibility. However, Mai’s failure to tell Sarah the rumour that Finbar had Annie Mangon committed to a laundry because his son “put her in the family way”, leaves Sarah ignorant of the danger James poses. Sarah learns that her rape and pregnancy must remain secret, if not, Finbar would have her “[b]uried alive” (159). Thus other women are left vulnerable to James’ sadistic lust. Sarah’s terrible fear of being locked up in a laundry and of the Cruelty Men taking her baby leads her to demonise Carmel “his witch of a wife” (232) so she can more easily seduce Dan. Thus we have a tyranny of fear and silence where women are set against each other in a desperate fight for survival.

From a young age Carmel learns to mind her every word so as not to inspire Finbar’s anger. She never shares her secrets, and her fury at Sarah is most likely amplified by repressed sexual desires: “The back of Sarah’s neck, warm and brown like an egg” (204). According to Emily, Carmel shows no anguish over her dead baby: “Did Carmel miss her baby? She’d never said” (279), yet we know it consumes her. Like the other townswomen seeking relief from their “nerves”, her dealings with the herbalist are clandestine. Carmel isolates herself, moving in shadows, trapped in her own tormented inner dialogue. In contrast, Emily would love to flaunt her relationship with the herbalist around town, but she is underage, so it must be kept quiet. Rose cannot fully confide in Charlie as she is incapable of connecting the sinister man that rapes her at night to her father: “My father had a twin. Not many people know that. A not-so-nice a man as him. They were alike but smelt different” (303), and Grettie insists on Rose’s covert abortion in order to protect the family´s respectability. And so the tragedy unfolds, and Rose dies alone by the riverside.

All this secrecy ensures that there is no possibility for these women to empathise with, nor help each other. They are seen to pay for the transgressions committed by men and a lack of male accountability is questioned throughout – Emily wonders about Aggie´s ex fiancé: “And where had he been when she’d needed him?” (198); and Mai explains: “Poor Annie didn’t get there by herself” (44). Thus, Sarah and Rose are both raped by dangerous patriarchs who are never exposed, Emily’s rape by the fat man is never disclosed, and Aggie is randomly beaten up by men who are never reproved. In addition, Carmel’s opposition to a cruel Catholic God is never expressed, illicit pregnancies are hushed up, and abortions are hidden. Nothing of import can be shared amongst the women and therefore bonds are only superficial and no united opposition can be formed. These women live in a climate of fear and silence which ultimately feeds the ignorance that maintains the dominant knowledge framework and divides the women in such a way as to reinforce the hegemony´s power over them.

Transference of Fantasy & Guilt

The carnival, the prostitute, movies, alcohol, illicit novels, and the herbalist’s laudanum, all act as pressure relief valves for the repressed community in The Herbalist, but a taste of what is forbidden increases frustration and anger at anyone in the community who openly deviates. The herbalist enters into this hegemony as a blank canvas on which the townspeople can draw their fantasies: “A charlatan, a magician, a fraudster, a saviour, who had appeared in the market to con them or heal them” (30). We glean from others his thoughts and understand that he feels his marginalisation: “he didn’t believe in the word ‘weeds’; it saddened him, like the term ‘itinerant salesman’” (111). Although he tries to give himself status: “Don something-or-other he calls himself” (28), Aggie sees his displacement: “He dreams of Indian boys, a ball of sun and dry earth in a place where everyone looks just like him.” (195). He will be tolerated by the hegemony until a scapegoat is required.

For Emily, the herbalist is “John Gilbert and Clark Gable all rolled into one” (139), and his flattery beguiles her: “he called me Cleopatra, said I should be bathed in milk” (119). She superimposes onto the herbalist a Hollywood version of the oriental lover, a “maharajah”, who has come to rescue her from a repressed life in a pious community. Although Emily believes that her sexual relationship with the herbalist was on an equal footing, she finds him guilty of hurting Rose and attempting the same with Sarah. However, she is aware that he is cleaning up the mess made by other men: “’Jesus help me.’ That’s what they all say” (237), and discerns Doctor Birmingham as the main culprit. Emily is soon made aware of the perils of confronting the doctor: “’You’re a very disturbed young lady. It’ll be no bother having you committed’” (272). Therefore, in her quest to seek justice for Rose, she points the finger at the more accessible culprit, the herbalist. Likewise, the repressed townswomen displace all their pent up anger onto him: “Hang him. Hang him. The women’s voices soared above the men’s” (300). Just as Rose cannot associate her father with the beast that rapes and beats her at night, so too the community is incapable of connecting the patriarchal hegemony to its hypocrisy and failure to punish the chief wrongdoers.

Gyn/Affection and Political Action

The control of written language has been in the hands of men for centuries, and therefore metaphor and language have become a tool for the dominance of the male voice. A victim of this dominance has been the concept of female friendship, or gyn/affection. According to Janice Raymond, the great need men have had to suppress and ridicule any expression of female friendship says more about the power of female friendship, and how men fear it, than anything else: “Constant noise about women not loving women is supplemented by the historical silence about women always loving women” (Raymond, 2001; 151). Raymond sees Gyn/affection as a political integrity which has political consequences. We can see how Gyn/affection manifests itself on various levels in The Herbalist.

There is strong gyn/affection to be found between Sarah and Mai: “I want you to have a few bob in your pocket, to live a little” (Boyce 46), between Emily and her mother: “Special people who didn’t need to talk much to know they liked each other” (6), and Birdie demonstrates gyn/affection toward Emily, ultimately leaving her sister´s shop to her. In contrast, Carmel´s denial of gyn/affection is self-harming and self-isolating. However, she regrets her behaviour towards Emily: “The child hardly got the time of day from anyone; there was no need for Carmel to join in” (30), and is relieved not to have achieved the termination of Sarah´s pregnancy. Unfortunately, she is pushed over the edge when she discovers that the money she gave Grettie paid for Rose´s abortion.

Although Aggie appears hard, her gyn/affection escapes her. She is the one to rescue Emily from her brutal rape by the fat man, giving him a black eye: “Leave the fucking child alone!” (188). We do not know whether the herbalist had a hand in Emily´s rape “First, I was safe on his lap. My laudanum whore. Then I was sore and torn beneath the glinting laughter” (188) but Aggie suspects him. From then on Aggie performs the role of mother towards Emily, albeit in a parodic fashion. In this way motherhood is not glorified. Emily and Aggie enjoy each other´s company and are affectionate in an unsentimental fashion. Aggie tries to make Emily understand that men will only bring her grief and that she has to fend for herself “You have a sewing machine and a good pair of hands; get them busy” (197).

Aggie can be likened to the old hag in Irish myth in which the goddess of sovereignty is lost and the rightful man cannot rule his people without her (Green, 2002). However, it is Emily who becomes intimate with the old hag, and both Aggie and Emily are empowered by this relationship. They save Sarah from the herbalist’s planned abortion, and in an effort to seek justice for Rose, Emily takes political action by waking up the town to what the herbalist has done. Again, similar to the goddess, Aggie consoles the damaged souls: “’They’re the frightened ones’” (Boyce 214). After caring for Rose following the botched abortion, Aggie’s heart is pierced by Rose’s words of “I love you” (251). This relationship between Rose and Aggie is fulfilled in a spiritual afterlife in which the ghost of Aggie finds Rose and they form a mother/daughter bond full of gyn/affection and banter: “You’re kind, Aggie. You didn’t always think that, you snotty thing, did you?” (223). Aggie’s role is to keep Rose’s tale alive: “While Aggie’s here you’ll never die”, and to help Rose remember so she can free herself of an internalised misogyny that made her believe “she deserved to be hurt” (283).

CONCLUSION

The very act of Emily appropriating the words of Rose´s last letter for the court case indicates the author´s acknowledgement of the artifice of the novel in attempting to speak for other women. I consider the voice of Aggie to be one of the most important voices struggling to be heard in The Herbalist, as the voice of the prostitute has been expropriated, marginalised, and silenced throughout history. Boyce uses the voice of Aggie to resurrect from oblivion the silent voice of Rose: “So I’ll tell your tale […] again and again till it no longer hurts you” (283). Rose is the voice of the betrayed, the innocent, the beaten, the hidden, the buried and forgotten:

You wouldn’t know it, but it’s my story. You won’t find me in the column inches. You won’t find me in the newsprint. You’ll find me in the gaps, the commas, the full stops – the small dark spaces where one thing led to another. I was afraid to speak, but now I’m not, for who’ll hurt me now? I’m past that, past touch. Isn’t that right, Aggie? (293)

Boyce’s novel encapsulates the power of a repressive and hypocritical hegemony to saturate the minds of its people. The punishment for non-conformity has been seen to terrorise women into a silence that nurtures ignorance and inhibits empathy, unity or action, thereby facilitating the patriarchal authority which controls them. Furthermore, we have seen how the repression of a community causes frustration and anger which is easily transferred onto women and society’s outcasts, resulting in a negation of accountability by the hegemony´s countless culprits. Without a doubt, this novel successfully raises the multiple voices of many of the marginalised women who were silenced throughout Irish history and shares with the reader the affection and solidarity which is to be found amongst women. The reader is left with hope for a more inclusive and just future in the form of Emily, who re-emerges to take her place in the community, albeit as an exotic outsider. Although we know she has a fight on her hands, we also know that she is the one to unravel this tapestry of oppression.

Maeve Evelyn Reilly M.A is an independent research scholar from Ireland. She is currently based in Granada, Spain.

WORKS CITED

Assmann, Jan and John Czaplicka. “Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique 65, 1995, pp. 125-33.

A Writing Blog. niamhboyce.blogspot.com/p/the-herbalist.html. 21 Oct 2018. Accessed 6 March 2019.

Bauer, Dale M. and Susan Jaret McKinstry. Feminism, Bakhtin, and the Dialogic. State University of New York Press, 1991.

Boyce, Niamh. The Herbalist. Penguin Ireland, 2013.

Connell, R. W., and James W. Messerschmidt. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender and Society, vol. 19, no. 6, 2005, pp. 829–859., jstor.org/stable/27640853. Accessed 10 March 2019.

Cullingford, Elizabeth Butler. Ireland´s Others: Gender and Ethnicity in Irish Literature and Popular Culture. Cork University Press in association with Field Day, Ireland, 2001.

Gardiner, Judith Kegan. “Female Masculinity and Phallic Women— Unruly Concepts.” Feminist Studies, vol. 38, no. 3, 2012, pp. 597–624. jstor.org/stable/23720196. Accessed 3 March 2019.

Green, Miranda. “The Celtic Goddess as Healer”, The Concept of the Goddess. Eds. Sandra Billington and Miranda Green. Taylor and Francis e-Library, 2002. Accessed 20 March 2019.

Greenwood, James. “The Wren of the Curragh.” The Pall Mall Gazette, 1867. www.kildare.ie/library/ehistory/2008/07/the_wrens_of_the_curragh.asp Accessed 12 March 2019.

Jackson, Pauline. “Women in 19th Century Irish Emigration.” The International Migration Review, Vol. 18, No. 4, Special Issue: Women in Migration, pp. 1004-1020. Sage Publications, 1984. jstor.org/stable/2546070. Accessed: 23 March 2019.

Kristeva, Julia, et al. “An Interview with Julia Kristeva: Cultural Strangeness and the Subject in Crisis.” Discourse, vol. 13, no. 1, 1990, pp. 149–180. jstor.org/stable/41389174. Accessed 30 March 2019.

Luddy, Maria. “Unmarried Mothers in Ireland, 1880–1973”, Women’s History Review, 20:1, 109-126, 2011. doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2011.536393 Accessed 15 March 2019.

McCarthy, Rebecca Lea. Origin of the Magdalene Laundries: An Analytical History. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2010.

Medina, José. “Toward a Foucaltian Epistemology of Resistance: Counter-Memory, Epistemic Friction and Guerrilla Pluralism”, Foucault Studies, Nº 12, pp 9-35, Kelvin Grove Queensland University, October, 2004 (Ed. 2011). as.vanderbilt.edu/philosophy/people/facultyfiles/medina-toward_a_foucaultian_epistemology_of_resistance.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan. 2019.

Morris, Pam. “Identities in Process: Postructuralism, Literature and Feminism, Julia Kristeva and Intertextuality.” Literature and Feminism, Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1995 pp136-160.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Visual and Other Pleasures, Palgrave, 1989, pp. 14-26.

O´Connor, Nuala. Blog. Inside the Wolf – the Niamh Boyce Interview. 22 Aug 2018. https://nualaoconnor.com/inside-the-wolf-the-niamh-boyce-interview/ Accessed 8 March 19.

Raymond, Janice G. A Passion for Friends: Toward a Philosophy of Female Affection. Spinifex Press Pty Ltd., Australia, 2001.

Rockett, Kevin. “Aspects of the Los Angelesation of Ireland.” Irish Communication Review: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 4. 1991. doi:10.21427/D7QH8X arrow.dit.ie/icr/vol1/iss1/4 Accessed 10 March 19.

Smelik, Anneke. “Feminist Film Theory”, P. Cook (ed.), The Cinema Book, London: British Film Institute, 2007, 3rd rev. edition, pp. 491-504. https://www.academia.edu/1648199/Feminist_Film_Theory. Accessed 5 Jan. 2019.

The Irish Examiner, 1 August, 2018. Buckley, Sarah-Anne. “Chilling effect of the ‘Cruelty Man’ lingers.” www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/views/analysis/chilling-effect-of-the-cruelty-man-lingers-859110.html. Accessed 6 March 2019.

The Irish Independent, 25 March, 2019. McElligott, Richard. The Rising Explained: The Proclamation and what it stands for https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/1916/the-rising-explained/the-proclamation-and-what-it-stands-for-34267711.html Accessed 25 March 2019.

The Irish Times, 5 June, 2013. Gleeson, Sinead. “The Herbalist who captured a market-town mob.” www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/the-herbalist-who-captured-a-market-town-mob-1.1416903 Accessed 06 March 2019.

The Sunday Independent, 26 Nov, 2013. Irish Book Awards: “Newcomer of the Year Award” 2013”. www.irishbookawards.irish/the-sunday-independent-best-irish-newcomer-of-the-year/ Accessed 6 March 2019.

Williams, Raymond. “Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory.” New Left Review, I/82, 1973. (revised text of a lecture given in Montreal, April 1973) jstor.org/stable/2546070 Accessed: 23 March 2019.

Writing.ie. “Niamh Boyce on The Herbalist and How it All Happened.” 6 June 2013. www.writing.ie/interviews/the-herbalist-niamh-boyce/ Accessed 6 March 2019.